After the Spike, by Dean Spears and Michael Geruso

Spears and Geruso taught me two important stylized facts: low fertility everywhere and falling fertility always. Low fertility is no longer confined to rich countries. Mexico now has lower TFR than the United States. Excluding Africa, the world as a whole is already below replacement. And moreover, falling global average fertility is a longstanding historical regularity, not just a peculiarity of the 21st century. As far back as we have reliable vital statistics, each generation has had fewer children than the previous one had (p 11). Our population has grown over the last few centuries because premature mortality fell, not because fertility rose.

These two stylized facts rule out lots of common monocausal explanations for low fertility. "The US birth rate is low because of the housing crisis." This can't be right because fertility is low almost everywhere, including in countries like China that have housing gluts. "The global birth rate is low because of hormonal birth control." This can't be right either because fertility has always been falling. France's baby bust began in the 1760s, long before modern contraception was available. Historians think Roman fertility fell below replacement before the common era.

Housing scarcity might very well contribute to low US fertility, and global fertility might be lower than it would have been had hormonal contraception never been invented. But it's not credible to claim that the US would be above replacement if only we built more houses, nor that global TFR would be trending up if not for the pill.

If there is a monocausal explanation for falling fertility, it has to apply everywhere and at all times since at least 1750. This is a tall order, but some explanations plausibly meet it. Here's one, offered by Spears and Geruso themselves—fertility has fallen because the opportunity cost of raising a child has risen. One way of seeing this is to appeal to the Linder Effect. As your income rises, you want to substitute away from time-intensive leisure and toward capital-intensive leisure. In a slogan, the more you make, the less time you spend meditating and the more you spend snowmobiling. Raising a child is more like meditating than it is like snowmobiling. It ties up a lot of time, and there's not much a parent can do to speed things up by deploying more capital. And if anything, childrearing is seemingly becoming more time-intensive, as measured by the number of hours parents spend caring for their children per day. Under these conditions, one would expect fertility to fall as incomes rise.

Does the opportunity cost explanation fit the stylized fact of low fertility everywhere? Sure it does. "The opportunity cost of a kid is growing around the world, not despite the fact that the world is becoming a better place to live, but because of it" (p 230). Whenever they talk about falling fertility in the developing world, Spears and Geruso's go-to example is Uttar Pradesh, India's second poorest state. Even there, GDP per capita has grown about 8% per year for the last decade, and over the last thirty years, TFR has fallen from 4 to 2.3 children (p 23). Does the opportunity cost explanation fit the stylized fact of falling fertility always? Yes, absolutely. Global GDP per capita has 14xed over the last 300 years. Each generation has gotten richer than the one before, so perhaps it's no wonder each generation has chosen to have fewer children.

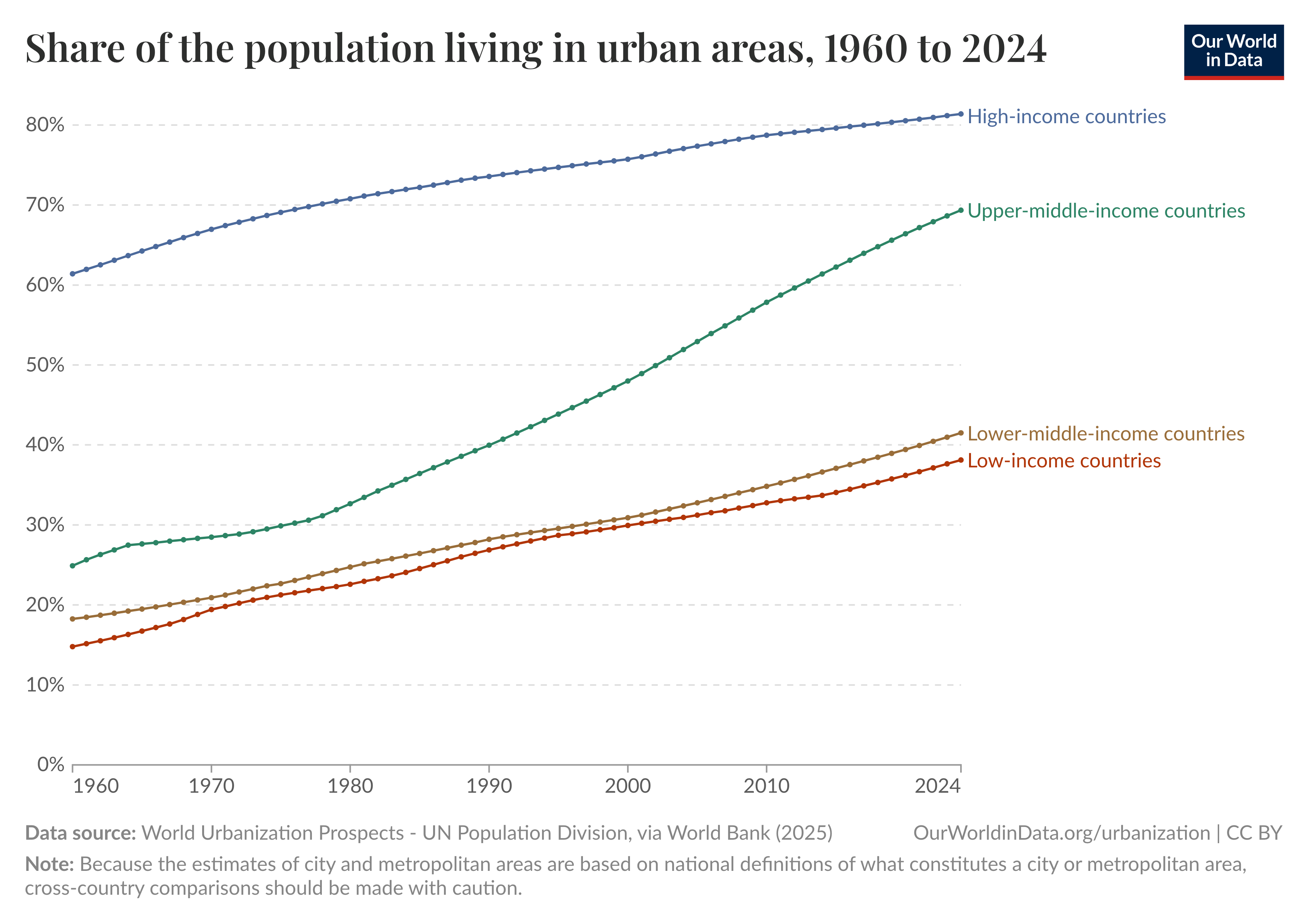

Another grand theory—maybe density in itself causes low birth rates. There's abundant evidence that the city has always been lower fertility than the country, even before industrialization, sustained economic growth, secularization, and most of the other factors that supposedly reduce births. Rome was possibly the most urbanized civilization in premodern history, and it suffered a centuries-long population collapse. In England, parish registers show urban women consistently had fewer children than rural women from the early modern period onward. And more granular data show the same pattern in nineteenth century America. If we grant that urbanization reduces fertility, the two stylized facts become predictable, since the share of people living in cities has long been rising and is now high—by historical standards—in rich and poor countries alike.

My overall view is that avoiding depopulation seems pretty intractable. It would require us to reverse a complicated, multicausal trend so robust that it has held for at least three hundred years all over the world. There's most likely no one variable we can push on to increase births in the long run, or if there is such a variable, it's per capita consumption or urbanization. Good luck convincing people to voluntarily impoverish themselves or ruralize to keep the population stable.

After the Spike is a good book, but also a frustrating one. The writing is defensive and hyper-neurotic, as if Spears and Geruso think their readers are out to get them. I understand why they wrote this way. They want to reassure all the NYT subscribers who bought the book that the authors are not Elon Musk. To my ear though, the whole thing sounds like it was written with a mysteriously guilty conscience.

I was frustrated and puzzled by the authors' argument (p 252) for caring now about depopulation that won't start til after midcentury. "The later the [fertility] rebound starts," they say, "the more depopulation precedes it," and thus the lower the steady state population when TFR settles down at 2 forever. But this is a weirdly circuumscribed hypothetical. If in the future we can push fertility all the way up to 2, I don't see any reason why we couldn't push it above 2, restarting exponential growth. As Spears and Geruso also say, "the number 2.0 is not protected by any unseen magic" (p 37). On their worldview, I really don't think it matters much when in the next century we start reversing population decline assuming we reverse it at all.

It's also frustrating to me how much time the book spends refuting bad defenses of depopulation. We should welcome depopulation because it means less pollution and climate change. Lower fertility is downstream of fewer marriages and stable relationships, which is actually good somehow. It's unethical to add new lives to a world where people sometimes go hungry or die from natural disasters. It reflects poorly on After the Spike's audience that the book has to give each of these arguments a chapter's worth of discussion.

I applaud Spears and Geruso for bravely wading into the swamp of population ethics. Their chapter 8 is quite clear, and I expect many philosophically uninitiated readers will find it persuasive. It got me wondering what the best strategy is to talk someone out of neutrality about creating happy lives. One is reductionism about personal identity plus the obvious goodness of saving a happy life. You say, saving a life is really just extending a life, causing person moments to be experienced that wouldn't otherwise have been experienced. There is no deep fact about whether two person moments belong to the same life. So it's meaningless to say that saving a person moment is good iff that person moment belongs to a life already in progress. Another strategy, suggested by Joe Carlsmith, is to imagine a happy life from the inside. This is especially easy if your actual life contains more satisfaction than frustration. Can you really say, with a straight face, that your creation was ethically neutral? That your failure to be born would not have been a loss ceteris paribus?

Why do I care about depopulation? I expect the future to look very different than Spears, Geruso, and their typical reader expect it to look. I do not think technological progress will grind to a stop as the human population ages because I think we're no more than ten years away from automating most R&D. I think this is the US's darkest fiscal hour just before dawn, when it's clear we're headed for a population bust, but not yet certain we're headed for an AI boom. Even from an ethical vantage, I have less reason to worry about depopulation than Spears and Geruso have because I expect digital minds to vastly outnumber human minds in the long run on any possible population trajectory. A couple billion missing happy humans are a rounding error on the trillions of digital minds Earth can plausibly support.

So again, why do I care? My main reason is that depopulation says something about our civilization's level of prudence or care for the future, and it ain't good. I think the population crisis is probably going to be fine, but on the consensus view of the future, we are collectively making a huge moral mistake. Most of the happy lives that could be lived will not be lived (on the consensus view) because the present can't get its act together and look after the future. To me, this is very sad. And it bodes poorly for our ability to handle other civilizational problems.

Related content recommendations

Reviews of After the Spike from Richard Chappell and Fin Moorhouse.

Jesús Fernandez-Villaverde interviewed by Sam Bowman on "the economics of the baby bust."

Alice Evans's excellent blog, The Great Gender Divergence. Evans's central story can't explain why fertility has fallen in the long run, but I think it does explain some of the decline we've seen in the last fifty years.

Peter Maxwell Davies, Lullaby for Lucy. This lullaby is the most beautiful work of art about depopulation that I know of.